FEATURE

May 4, 2022

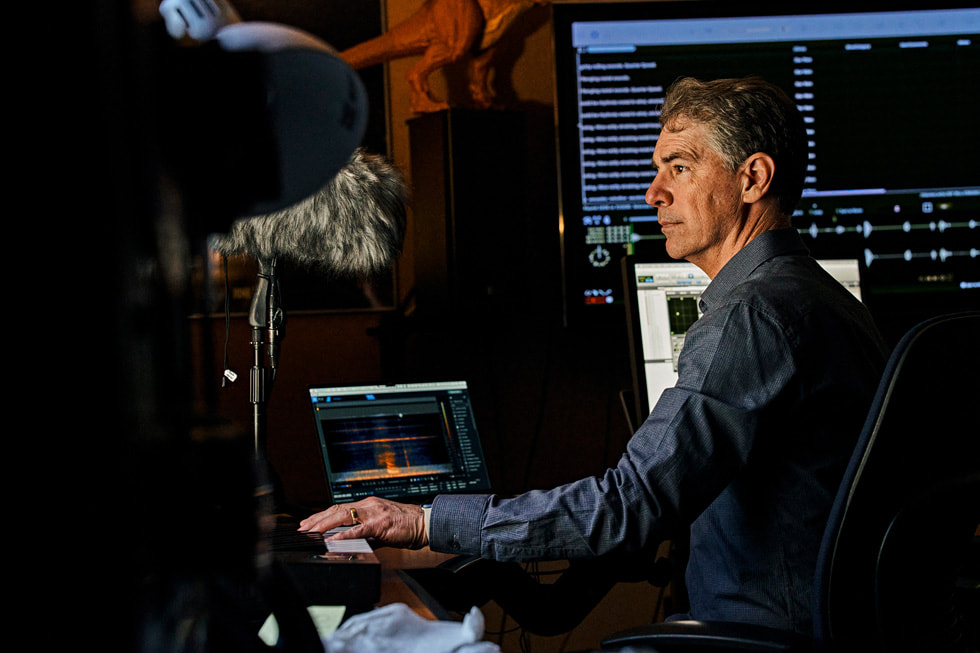

Uncovering the sounds of a galaxy far, far away with Mac

Skywalker Sound artists share their creative process, the origins of R2-D2’s voice, and their journey to building a vast sound library

In the rugged terrain of Nicasio, California, population shy of one thousand, visitors to this isolated corner of Marin County are surrounded by a spirit of limitless possibility. Miles of concealed cables and gadgetry teem underfoot.

This is the site of Skywalker Ranch, the vast facility owned and conceived by George Lucas, the creator of the epic Star Wars universe. The cornerstone of the ranch is Skywalker Sound, a world-class sound design, editing, mixing, and audio post-production facility. The 153,000-square-foot, red-bricked building, surrounded by vineyards and the man-made Lake Ewok, stands as a monument to the maxim, often repeated by Lucas, that sound is at least 50 percent of the moviegoing experience.

The sound library system Soundminer, which allows for descriptive keyword searches almost poetic in their specificity, keeps pace with Skywalker Sound’s ever-expanding library of nearly a million sounds.

Sound editor Ryan Frias gives a tour of Skywalker Sound’s central machine room, which he describes as “basically the brains of all the stage operations.” “As creative people, you don’t want technology to slow you down,” he says. “When you have a thought and you really want it out there on a blank canvas like that, you really need fast tools that can give you the results as fast as you think.” The studio’s force of 130 Mac Pro racks, 50 iMac, 50 MacBook Pro, and 50 Mac mini computers running Pro Tools all connect remotely to this central power source.

With the power of approximately 130 Mac Pro racks, as well as 50 iMac, 50 MacBook Pro, and 50 Mac mini computers running Pro Tools as their main audio application, along with a fleet of iPad, iPhone, and Apple TV devices, Skywalker is advancing sound artistry and reshaping the industry.

“I started out with a Macintosh SE, way back,” says Ben Burtt, the legendary sound designer of the original “Star Wars” films, the prequels, and the “Indiana Jones” franchise. “Word processing was a huge leap forward for me as a writer.”

“Sound editing in a way is really the same as word processing; cutting and pasting files,” Burtt continues. “All the experience I had on the Mac immediately gave me training for what came along in cutting digital sound. I started cutting using a Mac with Final Cut in the late ‘90s, and now have four Mac computers. Each handles a different process: one for picture editing, sound editing, manuscript writing, I’m completely surrounded. They’re labelled Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta.”

Meet the sound designers behind R2-D2, Darth Vader’s breath, lightsabers, and more at Skywalker Sound in this Behind the Mac documentary.

Talk to any artist at Skywalker Sound and it quickly becomes evident they all harbour a personal library of treasured recordings. “Sounds that evoke emotion are what we’re always on a quest for,” supervising sound editor and sound designer Al Nelson says.

For sound designers, even outdated equipment creates opportunity. “I love happy accidents and I love breaking technology and getting unexpected results,” says Nelson. “I love to play with digital systems that are clocking wrong, meaning the way the bits are flowing. It’s broken, it sounds like bad radio. I have a really old PowerBook, and it has certain old software I like to use; I can feed recordings into it and digitally break them.”

One never knows when inspiration will strike. A contractor who knew Burtt was always on the lookout for unique sounds once called to say he’d heard a strange, broken ceiling fan in an apartment he was servicing. Burtt’s recording of the wobbly blades later transformed into the ominous sound of the laser gates that momentarily divide Qui-Gon Jinn and Darth Maul during the climactic lightsaber duel in “Star Wars: Episode 1 - The Phantom Menace.”

Sources sometimes materialise from thin air. “I’ve had people write me on the internet and say, ‘My aunt has a really weird cough, do you want to record it for a creature?’” Burtt says. (Nelson refers to these components as “creature sweeteners.”)

When gathering field recordings in nature, supervising sound editor Baihui Yang stresses the handiness of having a MacBook Pro on-site. “We can bring the Pro Tools session with us in the field and watch and record and quickly put it together, to test whether it works or not,” she says. “If you bring all the recordings back to the studio, you don’t know if you’ve missed the moment.” Applications like Keyboard Maestro are also integral to her process, as is Matchbox software.

With a background in classical guitar, among other instruments, Nelson often seeks musicality in the outside world, as well as inside the mixing room. “We’re all musicians — either literally musicians, or musicians of sound,” he says. “Everything is very much a tonal approach or an orchestration approach. You can’t just throw noise at the screen; you have to articulate and pick your flavors in the same way that you would orchestrate something symphonic.”

The sounds we associate with Apple — the iconic F-sharp startup chime of a Mac, the swoosh of an outgoing email — share an essential, underlying characteristic with many of the most recognisable sounds of Star Wars, and that is one of activation. Think how often an idle droid bursts to life with warnings and bleeps. Or how the elegant, dormant handle of a lightsaber suddenly pierces into a glow. Or a ship, sputtering and lumbering through space, thrusts into lightspeed.

“What I learned from Star Wars was that Ben used all natural sounds to do science fiction,” says Gary Rydstrom, a seven-time Oscar-winning sound designer who started working at Lucasfilm in 1983. “He kept sounds in the Star Wars universe gritty and realistic, based on real sounds you would manipulate into something you’d never heard before, which was inspiring.”

A key distinction in Burtt’s work is the element of performance. “When it comes to fantasy sounds, especially — alien voices, creatures, weapons, strange things of the sort — a performance helps,” Burtt says. In the earliest stages of finding the voice of R2-D2, which set the standard for how sound design can influence character development, Burtt felt increased pressure, knowing the droid would be sharing scenes with Alec Guinness.

“When I sat down and started experimenting with R2 on the first film, suddenly I realized that I’m in dialogue,” Burtt explains. “The timing is very important. Once we realized we had something that was working, the picture editors went back through the movie and started re-cutting many of the scenes, changing the timing ever so slightly. It began to figure into the actual pacing, as any dialogue would.” Burtt continued to refine the performance in the prequels, for which he served as both sound designer and picture editor.

“Sound designers actually create sounds from nothing,” says supervising sound editor André Fenley, whose extensive credits at Skywalker Sound include the iconic dinosaur sounds from the original “Jurassic Park.” “They’re going out and recording the most weird things that you can think of, and they take those raw sounds and manipulate them and bend them and break them and turn them upside-down and see what they get.”

As the artists at Skywalker Sound have settled into the digital age of filmmaking, their advice for both aspiring and professional filmmakers is boundless. “I tell young people who want to work with sound in movies, ‘You should listen to the world around you and build a sound effects collection,’” Burtt says. “Get a recording and classify it, because any time you build a library of sound, you are making creative choices. The other thing is that because there are plenty of inexpensive applications that you can have access to now on your iPad or your MacBook, that you can actually do all kinds of cutting and sound-mixing at home. I could never do that. If I was a teenage filmmaker again, I’d be amazed. I’d have drones, I could do all kinds of sound recording. I could do none of those things in my formative years.”

Nelson even attests that iPhone recordings are “perfectly useable” in a professional context.

“However you do it,” Rydstrom says, “think about sound early on, because it’s one of your storytelling tools. I will argue it’s one of the more efficient storytelling tools, once you get into the shooting and cutting.”

“You can tell a lot of the story with sound in a way that is less expensive than visuals, usually, and sometimes more emotionally powerful,” Rydstrom continues. “If you’re interested in sound or filmmaking, you can record 4K+ video on your iPhone. There’s no excuse. The stuff that’s part of our day-to-day lives is the same stuff you need to record sound and make movies. That’s the real revolution. Ultimately, it will democratise the whole process.”

Share article

Media

-

Text of this article

-

Images in this article